Filled with glittering LED sculptures, Pace Gallery doesn’t look much like the other austere Chelsea galleries on West 24th Street. In his first solo show with the gallery, New York-based light artist Leo Villareal subverts the plain white cube, turning it into a cave sparkling with ethereal light. The pieces seem to breathe, their shimmering patterns dictated by some alien rhythm. In actuality, they’re manipulated by complex algorithms Villareal programs and then sets loose, allowing the patterns to iterate and morph.

Villareal improvises with code the way a jazz musician might explore the limits of his instrument. “The epiphany I had was connecting software and light,” Villareal tells Creators. “To add software and code to that and start to sequence the light was very, very profound, but it took me many years to get there.” The pieces at Pace Gallery are a journey through Villareal’s explorations, offering a sampling of his work and a glimpse of how it might evolve.

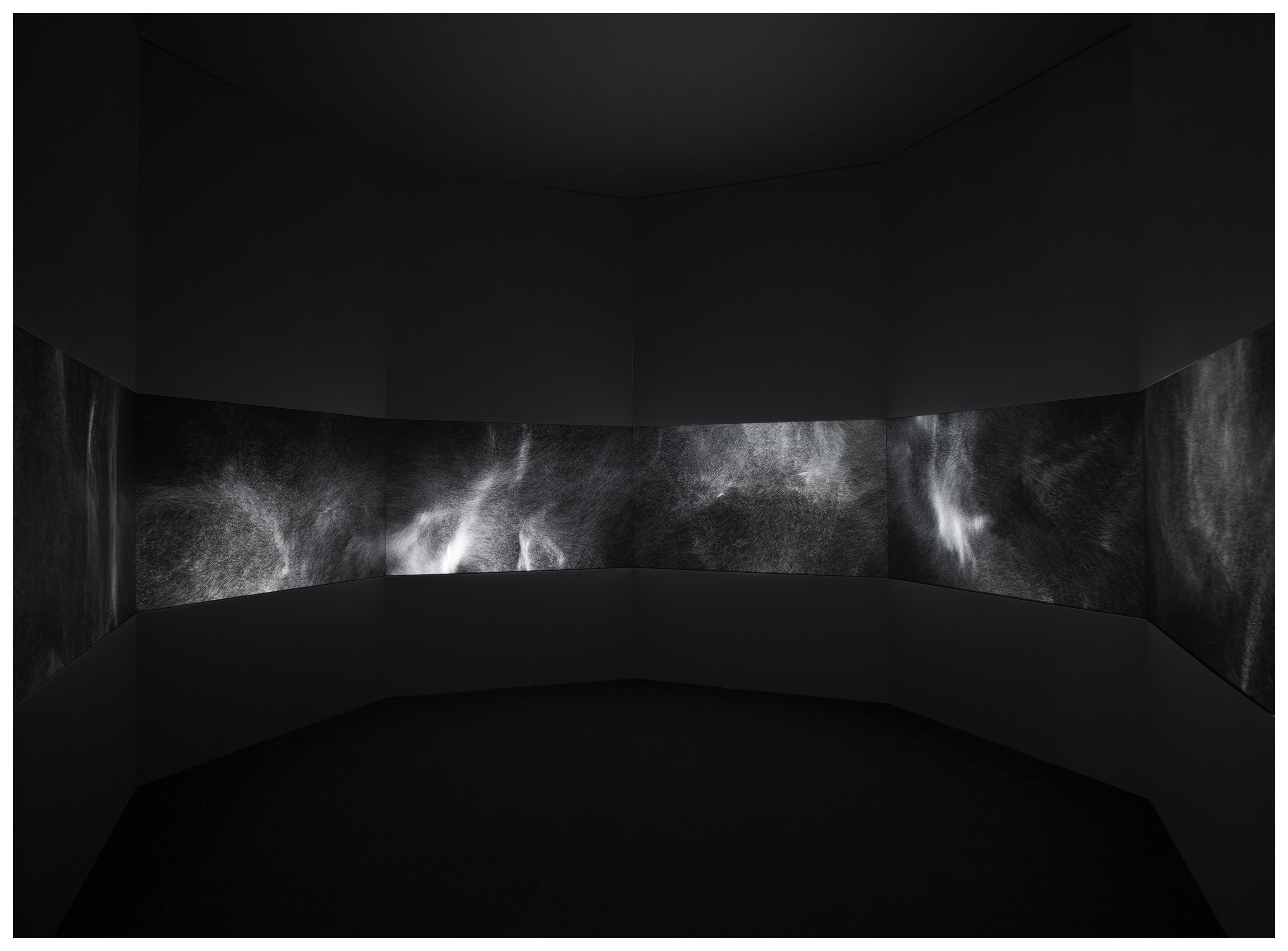

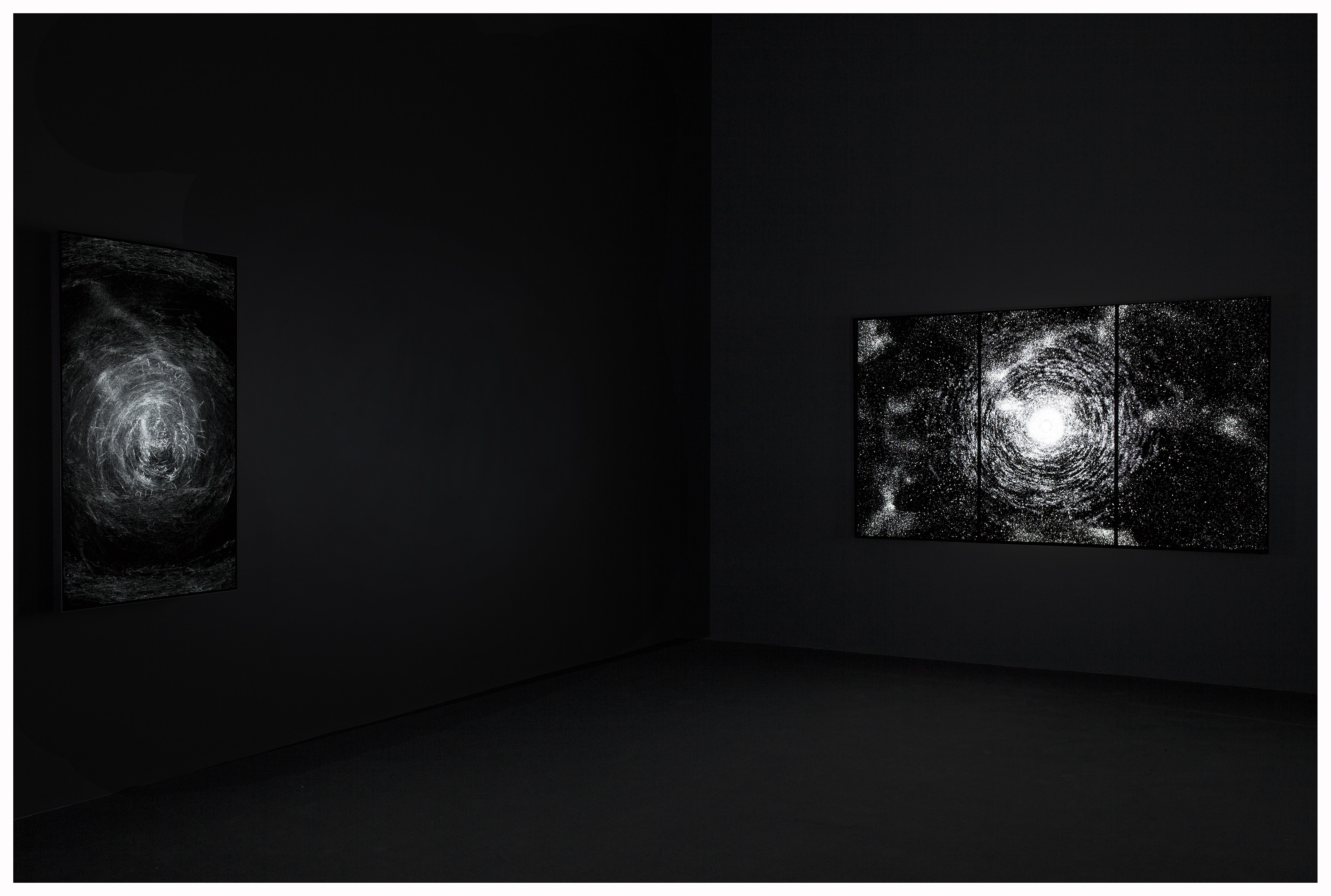

The show opens with the artist’s Cloud Drawings, minimal wall-mounted rows of vertical LED’s, reminiscent of The Bay Lights, the artist’s massive takeover of San Francisco’s Bay Bridge. In an adjacent room hangs Ellipse, an array of hundreds of mirrored stainless steel rods suspended from the ceiling, dripping with light like celestial stalactites. Around a corner, in a darkened gallery, 4K screens and immersive projections display mesmerizing pinpoints of swirling luminescence that could just as well be galaxies exploding as particles colliding.

Installation view of Leo Villareal, 537West 24th Street, New York, May4–June17, 2017, Photography by Kerry Ryan McFate, courtesy Pace Gallery

Villareal’s practice stems from a technical background. After grad school at New York University’s Interactive Telecommunications Program (ITP), he wound up working in Silicon Valley. But it was Burning Man that unleashed his fascination with light. Villareal had gotten disoriented in the dust and the dark of the desert in years prior, so for Burning Man in 1997, he built a glowing sculpture to find his way home on the Playa. It was a practical solve, but the visceral reactions of other Burners made Villareal realize he was onto something.

The artist describes his pieces as “digital campfires,” a primal gathering point for viewers to congregate around and get lost within. Just like fire dances and changes, seemingly with a mind of its own, Villareal uses proprietary software and hardware to program his sculptures to mimic organic life through emergent behaviors.

“Some of my early inspirations came from things like mathematician John Horton Conway’s Game of Life, wherein a simple set of rules produces incredibly complex patterns you could swear were from something in nature, either something very small under a microscope or something huge like in the cosmos,” Villareal says.

Installation view of Leo Villareal, 537West 24th Street, New York, May4–June17, 2017, Photography by Kerry Ryan McFate, courtesy Pace Gallery

Villareal plays God in a simulated universe, setting parameters within his algorithms to coax life out of cold, hard numbers. “I’m waiting for that 1% of the time when something interesting happens,” he says. “I’m harvesting these moments and these discoveries, and they all become part of the final works.”

“Somehow it really feels like it has personality, and I think it’s because I’m using physics and a lot of things people are familiar with in their daily lives, like looking at a sunset or staring at water or waves,” Villareal continues. “These kinds of things are built into us from nature to somehow elicit a response. I’m accessing that same area of the brain to bring that out, by somehow harnessing these natural and organic systems.”

Next up, Villareal will embark on the world’s largest public art installation. In December 2016, London’s Mayor Sadiq Khan announced that Villareal and architecture practice Lifschutz Davidson Sandilands won the Illuminated River Design Contest with a plan to infuse London’s 17 bridges, from Tower Bridge to Albert Bridge, with light and color. It’s an apt next step for the artist, who believes in the power of monumental public art.

“These things have a presence, and people want them to be a part of their lives,” he says. “We’re all enmeshed with digital technology, and this is another instance of that, but it’s somehow pleasurable, because you don’t feel like you’re ‘on rails,’ being force-fed a message. It’s a bit of a cliche, but public art brings people together. When you see people down on The Embarcadero looking at The Bay Lights, complete strangers can’t help but talk to one another about it, because it is sort of awe inspiring. It makes people feel good, and I believe in that.”

Installation view of Leo Villareal, 537West 24th Street, New York, May4–June17, 2017, Photography by Kerry Ryan McFate, courtesy Pace Gallery

Installation view of Leo Villareal, 537West 24th Street, New York, May4–June17, 2017, Photography by Kerry Ryan McFate, courtesy Pace Gallery

Leo Villareal is on view at Pace Gallery in New York City through June 17.

Via Creators