Related post

LIGHT INSTALLATION “LEVEL” TAKES THE AUDIENCE BEYOND THE PHYSICAL REALITY

Feb 22, 2017

|

Comments Off on LIGHT INSTALLATION “LEVEL” TAKES THE AUDIENCE BEYOND THE PHYSICAL REALITY

4070

Skaters Put an Art-Deco Half-Pipe Inside an Iconic 1920s Skyscraper

Apr 27, 2017

|

Comments Off on Skaters Put an Art-Deco Half-Pipe Inside an Iconic 1920s Skyscraper

2257

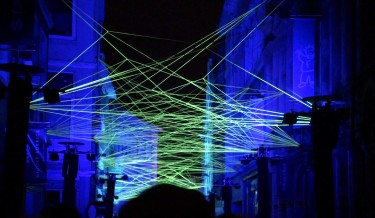

Ghent Light Festival 2015: Video Collection

Feb 23, 2015

|

Comments Off on Ghent Light Festival 2015: Video Collection

3222